Guest post by Dr Jackie Webb, Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada.

Like many in academia, I battle with impostor phenomenon (IP). More commonly known today as impostor syndrome, IP revolves around feelings of inadequacy, including anxiety over intellectual phoniness and the persistent self-doubt in abilities. Often viewed as an internal struggle within individuals, IP remains a largely unaddressed issue in academia, with limited support for those experiencing it. However, this is a universal problem affecting the research strengths of institutions as chronic IP is unknowingly limiting the success of highly capable early career women scientists.

Reasons why women feel like an impostor

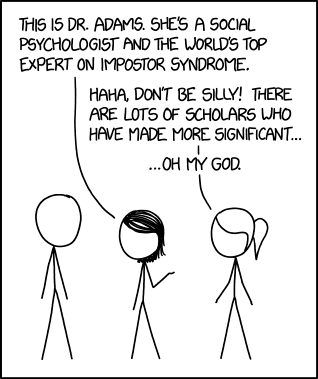

Research shows that a higher incidence of women in STEM careers experience IP. In fact, the origin of the term was first coined by a female psychologist, Dr Pauline Rose Clance, who found that IP was rife in a subset of 150 high achieving female students and scholars (Clance and Imes 1978).

Image source: XKCD

Although it is now recognised that individuals of any gender and background can experience these debilitating feelings of low self-worth, impostorism can be more detrimental to women advancing in the workplace (Young, 2011). There are many reasons why women in science can feel like impostors. This can be because science is still viewed as a very much male-dominated culture. Women are navigating careers and moving up in leadership roles, but men still hold the majority of these positions within higher education. With this lack of representation, it is no surprise that women in academia feel intimidated and sometimes unwelcome. The competitiveness of science can also in-adversely create a toxic work culture. The many different objective measures of success in academic roles can heighten the blow of rejections, and this combined with unmoderated criticism from all directions can greatly devalue an individual’s self-worth.

Given that many early career female scientists feel overwhelmingly insecure in their roles, it's important that we create more awareness so that action can be taken to support women battling with IP. I'd like to share my own personal story with IP and offer some advice in what I have found helps with managing it.

My story

My young age and self-imposed high standards seeded a lot of my own feelings of self-doubt as I progressed through undergrad and graduate school. During my undergraduate degree, my confidence went downhill pretty fast. Straight out of high school and moving from a small Island in the south Pacific to the Australia mainland, university was a scary time for me and a huge adjustment. Many students were mature age in my Environmental Science course, and to me everyone appeared a whole lot more comfortable in themselves which heightened feelings that I didn't belong. I did not know what IP was at the time but looking back, I had it bad.

Despite achieving high grades, my insecurity became so extreme that I was seriously considering dropping out at the end of my second year. A lot of convincing from my now husband kept me going. I'm glad I did stay on as in my third year I found some units that really sparked my interest, enough for me to forget about IP feelings for a moment, and this founded the path to a career in research.

I went on to complete my honours and PhD with some inspiring and highly supportive scientists. My work in carbon biogeochemistry of ecosystems was very rewarding. I experienced more that feeling of accomplishment that comes with unravelling findings from your own data and publishing in peer review scientific journals. I loved the work and was convinced I had found my calling. However, I often found myself intimidated by my more senior peers and I was still questioning my own abilities. I put myself under a lot of pressure with my both my work and personal achievements. I criticized myself every day and this would often lead to feelings of not being good enough, no matter how insignificant the task. Once again, I was one of the youngest lab members and everyone was highly productive and achieving great things. I felt the most inexperienced and sometimes thought I might be a burden to my supervisors and team members.

Then I started my postdoc at the ripe young age of 25. After successfully completing my PhD in three years, I found myself in a new highly qualified role, in a new country where I was not a student anymore, and surrounded by highly qualified colleagues. The stakes are higher in terms of establishing your career during a postdoc, with research outputs and more managerial responsibilities. Despite having the qualifications and proven track record on par with any other postdoc, I was super conscious of my age and at times felt I wasn't deserving to be at this career level. The age gap felt wider here as I was in North America where graduate school generally takes much longer. It didn't help that I was often mistaken for a student within the institution and at conferences, which lead to thoughts like "maybe it’s because I speak naively and just don't have the maturity that comes with being a qualified scientist"?

During my PhD and postdoc, I did learn to push myself into opportunities that I did not feel prepared for, and found myself rising to the occasion and succeeding. I handle paper rejections and critical reviews of my work much better now by letting those first emotions arise, acknowledging they are unrelated to me personally, then pushing them aside once I'm ready. I have been fortunate enough to have really supportive colleagues who made a point of letting me know my value to the team. I am very grateful for these ‘believers’ and aspire to be a believer to other students one day. IP feelings still arise but I learn to just acknowledge them and precede anyway. There are still some falls and mistakes made along the way, but this is the only way to keep moving forward in my role as a research scientist. We are all our own worst critic, the trick is to not let this become debilitating.

Below is a summary of advice on how to lessen the effects of IP based on my personal experiences.

Acknowledge that it is OK to be critical of your work, but not of yourself. Understand that doing a PhD is HARD. You are pushing the boundaries of human knowledge and advancing science. This process involves engaging in a critical mindset but this should be aimed at your work and not your personal capabilities.

Take some time to yourself to acknowledge every little success. Academia has a very forward moving work culture. Often before we finish one thing we are already looking onto the next 10 things. It's easy to lose sight of hard work you have already accomplished. Or the stepping stones you built to set the foundations of your current project.

Accept compliments and avoid responses of self-deprecation. It is far more common to find women de-valuing their compliments compared to men. Attribute your success to yourself, and not to external factors.

Give compliments. This one is more for the supervisors, mentors, and PIs out there. Give your students and junior colleagues positive feedback. Too often we focus on how things can be better and, perhaps unknowingly, set high standards to be successful. If a student has done well, or have shined in a task, let them know. It's not about feeding egos, it's about fostering a supportive work environment where everyone feels valued.

I'm not a fan of the saying "fake it until you make it". I ignore this advice as this just reinforces that voice in your head saying you're a fraud later on when you have earned your position. In my experience, performance and success is governed by how you apply yourself in the moment. Even if it is a first time task, like writing a grant or giving an oral presentation, you are not faking it by any means. Putting your best self forward in any challenging task is what defines "making it".

Take some time to internally reflect and try to identify the reason for feeling like an impostor in a situation. You can become overwhelmed by the feeling if you are unable to identify the external source. Sometimes it may be something strikingly obvious why you are feeling uncomfortable, like realising you're the only woman at the meeting. Then set that aside and engage with the moment.

Break down big tasks, such as that PhD, into smaller more manageable chunks. You are likely to be setting yourself up to disappointment if you try and tackle a huge project over several months. During my PhD, snack writing made things really manageable for me as I felt crippled if I thought about my PhD in its entirety. Snack writing is a practice I use all the time now in my work, and even completing just one paragraph of writing in a day leaves me with a feeling of accomplishment.

This one is really important. Talk with other women and you'll find you are not alone. Through talking with other female colleagues, I found out that I was most certainly not alone in feelings of IP. Being able to express your fears and doubts with understanding women has really helped put me at ease. Speaking out, listening, and supporting is something we can all do with a lot more off.

And finally, put yourself out there and take a seat at the table. Acknowledge that you may not feel ready but do it anyway. It's amazing how much we can rise to the occasion and achieve great things when we put ourselves out of our comfort zones.

In summary, I believe overcoming IP is a lot about practice, as with a lot of things. Practice pushing yourself into uncomfortable situations (for me this was giving talks at University and conferences), practice acknowledging your doubts, practice recognising your achievements, and eventually you’ll see that you can. IP can be a paralyzing fear as suffers usually keep their feelings private. As a woman, I think opening up to friendly female colleagues about insecure feelings really helps with this overcoming-IP practice, as we likely share similar fears and doubts.